Page 65 -

"With her famous poster for JOB cigarette papers, Jane Atche set a striking counterpoint to the portrayal of women by men that was typical of the period."

Page 67 -

In 1853, The New York Times ran a brief article applauding the establishment of The Ladies Paper, a publication that employed women to create the ‘typography’ of its pages.The journals business management and editorial content remained safely in the care of men, while the ‘merely mechanical routine’ of typesetting was delegated to women. Praising this arrangement, the write explained that giving women opportunities for employment would improve their lot far more than arguing about lofty concepts of ‘Women’s Rights’ or the ‘intellectual equality’ of the sexes. What women really needed was paid work.

‘The arts of design’ the write proclaimed, ‘are all attainable by female as well as masculine skill.. In short, wherever muscular strength and great powers of endurance are not required, there women may venture with entire propriety and there they ought to be.’

Page 78 -

A long tradition of posters promoting social and political causes or cultural events.

Suffrage was the central issue for feminism in the early twentieth century. As art historian Paula Harper has pointed out, the suffrage posters of the 1910s (as opposed to cartoons and other graphic work) tended to be conservative in their rhetoric and visual style.

The strategies chosen by the posters’ publishers and designers aimed not so much to agitate as to reassure. While many nineteenth century feminists had taken a revolutionary stance against society’s norms and in situations, the suffragists of the 1910s pleaded their cause by suggesting that the women’s vote would strengthen rather than destroy the existing family-based culture.

Bertha M.Boyes 1913 poster ‘Votes for Women’ is symmetrical in design, reinforcing the sense of serene stability emanating from the statuelike figure at its centre; the orb rising behind her head is both sun and halo, suggesting unambiguous warmth and virtue. The posters slogan appears not as an argument or battle cry, but as an unassailable truth, an inalienable right whole time had come.

Posters, buttons, and bumper stickers, carrying such slogans ask ‘Women's Liberation IS the Revolution’ and ‘Women are not Chicks’ suggest that second wave feminism was its own battle within the broader counterculture.

Page 105 -

Since the beginning of the modern era and parallel to the emergence of the women's movement, women have worked in various fields of graphic design. Although they did not initially gain access to institutionalised forms of training and education, which meant that they were unable to enrol in full courses of study at art academies and were likewise excluded from vocational programmes, women nevertheless succeeded in professionalising their training through special courses at academies and private schools.

Women were marginalised by avant-garde Modernism, which serves as a primary reference for design history. Modernist groups in Europe were male associations.

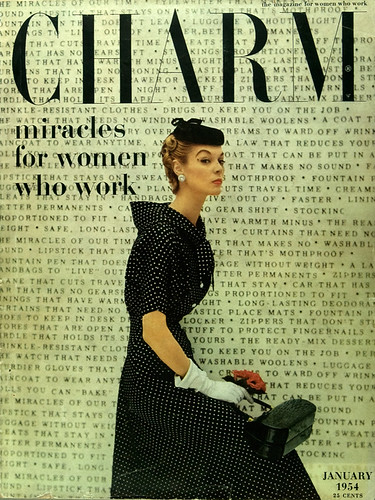

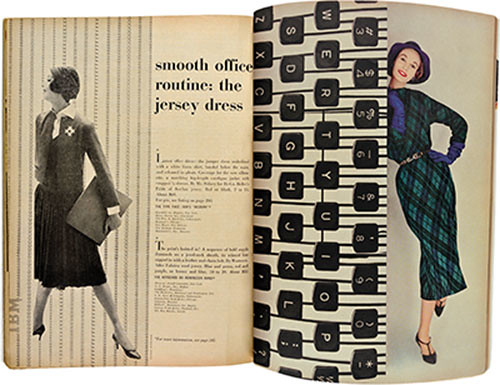

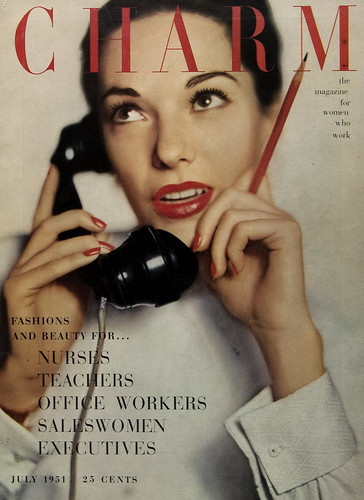

By contrast, female graphic designers were strongly represnted and much more visible both in the applied arts at the turn of the century and in the booming market of illustrated magazines, journals, advertising and popular culture during the 1920s. During their lives, they were held in high esteem by their clients and the trade press, yet few of them entered the canon of design history.

Page 165 -

Cipe Pineles was a design innovator. Why, when the history came to be written, was she left out?

Page 227/228 -

Irma Boom Interview

Is graphic design still a boys’ club? Or in other words: is it still harder for women to become successful.

Well, I don't think it is any different than in other fields. But it is indeed remarkable: at schools you see many women, but less in professional life. Certainly, getting somewhere demands time, stamina and a belief in what you are doing. I spend seven days a week on my work. People always say to me: ‘You are so ambitious!’ But I never feel that way, I love my work.

But there are still so few female members in ADC and AGI!

AGi has always been mostly dominated by male poster designers. I am a member of AGI - Wim Crouwel and Anton Beeke nominated me. And when the AGI accepted me, the chair of AGI Netherlands actually cried! ‘Finally a woman’ he said. That was in 1997 - so recently! I was also the first woman to do the Stamp Books and the Holland Festival posters. But I realised this only later. I didn’t think about it at all.

Page 233

Paula Scher Interview

Have men changed?

They work better with women than they used to. They are less condescending and accept that women make terrific designers.

Page 237, 238, 239, 240, 241 -

Sheila Levrant de Bretteville

Sheila, you are seen as and call yourself a feminist. What was it that interested you in the beginning?

In 1970, a liberation movement had 'my name' on it, the 'women's liberation movement'. I was fascinated by looking at women as a category of people who have been under valued. That was a new and information rich way for me to understand what being a woman had meant to others and to me. At that time, and since then too, I have never seen myself as being less because I was a woman. Even when men treated me as an object, that did not make me feel less than who I was. That just made me think less of them!

How has the notion of the term 'feminism' changed in the last forty years?

During the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s it seemed necessary to use the word 'feminist' to bring attention to women as a category of people. The word 'feminist' marked the intent to make public and known what we were leaning about our lives as women and they work we were doing. The reclaim women who had been overlooked, undervalued and misrepresented. The word 'feminist' was and is still a positive signifier from my perspective. Even those who attached what they might think were 'unfeminine' behaviours to that word would notice that the word reminds them to pay attention to women, whether they like particular women or not.

In Germany, some women recommend not talking about gender issues any more. They say that the necessary legal changes have been made and now only time is needed to achieved equality. -

Cf. Ursala Marz: Lasst mich in Ruhe! (Leave me alone!) In: Die ZEIT, No.22,26.5.2011, p.49.

Some things have changed, yes. More of the young men are feminists, for instances young men who have zero tolerance for sexual harassment. And more older women are visible in positions of authority and power - although most are indistinguishable from the men but for their gender. And that is not surprising. other women use their positions in new and fresh ways and that is inspiring. That change has come results from quite a lot of work by many people. Letting up the pressure to change towards more equality under the law is not a good idea. People forget how the change comes about. Critical mass is necessary. I have always thought about feminism as making new ways of working and thinking about people all along the spectrum from male to female - and that is happening.

But for all women to be treated equally under the law, in their streets and homes, we need a critical number of people willing to keep issues of women present in the press, on the internet everywhere in every medium. - people forget to pay attention to whether other women are doing as well as they are. Just like those women designers who forget about women unlike or less successful than they are themselves. To be a feminist, you have to identify with women beyond yourself and beyond your own success. I had to learn that as well: It took quite a lot of effort on my part as an adult to understand the boredom of a suburban woman. I lived in the city in a household where everyone worked - the women and the men. Betty Friedan wrote about the pattern of bored middle class women in suburbia, not working-class urban women.

Still today, many successful female graphic designers have no children. Is it easier to be successful without children? And if yes, is it only because of the lacking time?

Being able to focus only on your work (no children, nobody to care for) can make you more successful - but not always! Having children is not the problem, nor is not having them the soluton. Managing time well is a necessary skill everyone needs and especially anyone with children. How much parents of small children can manage - and not - depends on the kind of help they get.

But even if women decide not to have children and work with the same enthusiasm as men, why do they not make it to the top as often as men?

Men often do not notice there are no women around. Yes, there are still mostly men at the top. Since they do not often notice that women are missing up there, it is important to constantly remind them to include other kinds of voices and ways of dressing and speaking than their own - women.

One last question: what role do men play in the process of equalisation - Is the importance of them being part of the process emphasised enough?

Supportive men who act on their feminist values have always existed. The role men have played and will play in the process of equalisation should be given public and loud applause! A simple thanks suffices for some. It is important to see what all have to gain from the inclusion of women as equals and in equal numbers at the table - in the professional as well as the private sphere.

Page 319, 320, 321, 322 -

Paula Scher (The Boat)

1000 words on the subject of breaking into and working for the boys' clubs.

tokenism - the practice of making only a perfunctory or symbolic effort to do a particular thing, especially by recruiting a small number of people from under-represented groups in order to give the appearance of sexual or racial equality within a workforce.

- Every time I give a presentation to a design group, I'm asked what it's like to be a woman blah-blah.

- As i'm invited to give the presentation, I'm told that women will really want to hear about being a woman blah-blah. They go like this: ‘Hello, can you judge the annual peoria Hang Tag competition, please say yes because we need a female juror.’ How I envy my male partners who are invited to speak based on their achievements and prestige as opposed to their sex. I cannot separate my own achievements from being a woman blah-blah.

- I don't believe that pursuing this course while happening to be a woman is particularly special, nor do I believe there should be special standard for women. I haven't ‘broken’ into boys’ clubs. I am merely following the path of a life in design at a time when doors are opening for women, not merely because they are women, but because they are successfully following that path.

- There was Donna Shalala standing next to Bill Clinton and Al Gore and some male senators and newly appointed cabinet members. The same week in the same New York Times, I read about how women's groups were upset with Clinton for not appointing enough women to Cabinet posts and Clinton railed against the quotas. All of this served to diminish the wonderful accomplishments of the excellent women who were appointed. One woman in the group. Two women in the group. Their individuality is lost and all one sees is the strangeness of scale.

- A profession that has long been dominated by men is changing. There are simply more women. There are more women who are terrific designers, more women running their own businesses, more women corporate executives, more women changing the scale of things and appearing out of scale in the process.

- There are also more underpaid women, more women juggling careers and motherhood, more women who feel squeezed out in a bad economy, more women who are resentful of their lack of success ‘because they are women’.

- Women's issues in design are focused on scale. We count the numbers, look at the statistics, and demand change, and all the while change is occurring. Change doesn't come in one great thump. It comes one by one by one, and it looks kind of funny. And then it doesn't.

Page 325 -

Ellen Lupton - 'Sheila de Bretteville became chair of the graphic design program at the Yale School of Art in 1990. In addition to encouraging her students to draw on their own personal experiences, she believes that designers should interact with their audience and should consider the social consequences of their practice. According to de Bretteville, producing design in collaboration with one's audience is a feminist act, because it draws on values of intimacy and cooperation associated with women's culture.

Page 333 -

Veronique Vienne

- Ellen Shapiro, a New Yorker graphic designer who makes her high profile clients more visible, once tried to challenge the known content of a universal image. 'I saw this mother and a child in the subway' she tells. 'The baby was dressed in pink, with matching ruffles, bonnet, socks, and booties. On impulse, I wondered what it would be like to ask the mother if her baby was a boy or a girl.' She never found out - questioning some of our shared assumptions is simply unthinkable. Confounded by the irrevocable character of her perception, she realised that gender is first and foremost a powerful optical illusion.

Page 355-356

Higher Education - Alissa Walker

The New School

Thirty five years ago, resources were extremely limited for design educators looking to restructure or start a new program. Most universities borrowed heavily from the traditional Swiss or Bauhaus schools, which, although historically valuable were losing ground to the counterculture of the late 1960s. These institutions were regimented, rigid, and run almost exclusively by men.

In 1971,

Katherine McCoy became one of the first women in the country to head a graphic design program, a position she shared with her husband, Michael, at Cranbrook. Given the first truly alternative academic experience for design students, one suddenly infused with social and cultural relevance.

`Kathy flew under the radar', says

LOUISE SANDHAUS, director of graphic design at CalArts. 'Any transformations she made, I don't think they were as noticed. I don't think there was anyone there to stop her because no one was taking it seriously enough.' Slowly, other graduate programs began to take note of the experimental education that was churning out a very different kind of designer. `Cranbrook was almost a tribal environment,' says McCoy. 'It was a demonstration of the 'it takes a village' idea.' Cueing their own careers from McCoy's example, two women who graduated during that time went on to disseminate this approach in schools on opposite sides of the country.

MEREDITH DAVIS headed to Virginia Commonwealth University, then to North Carolina State, where she was the first female chair of the graphic design department and currently one of the nation's most active figures in design education. Davis had multiple degrees in education and design and was naturally drawn to the classroom, but for her classmate

LORRAINE WILD, the path was more serendipitous.

When Wild was lured to CalArts three years out of grad school, she found herself immersed in a liberal academic environment pioneered by

Sheila. DE BRETTEVILLE establishment of a women's design program in 1971, and the previous tenures of APRIL GREIMAN and LAURIE HAYCOCK. Drawing heavily upon their Cranbrook discourse, Davis and Wild. engineered graduate programs that both lured and produced the most influential design educators in the country.

A Woman's Work?

The field of education has traditionally been conductive to women who preferred its schedule for tending to households. Yet for a designer, making the choice to return to academia is often not one of pure convenience. Although education does afford flexibility, most design educators maintain practises on top of their faculty commitments. For

these women, becoming active in education was a way to push issues that were important to them, and in a safe and collaborative environment - one that was, at first, slightly more accommodating than the professional arena. 'I think where maybe myself and other women educators were going was not to deny the way the design field worked, but rather to open it up', says

Lorraine Wild. 'It was really critical to me that we look at design as culturally important, socially important, and not just a trade practice. Why was it that women were doing that? All I can think of was because other areas of design were less flexible and not as open to reform.'

Sandhaus, who assumed the graphic design directorship at CalArts after Wild,

notes that at the time, women were the outsiders in design. 'I think because women felt so ostracised from their environment and could feel a sense of not belonging, in some ways we started our own world. A world we thought was actually going to acknowledge reality.' `If the doors are closed to you because you don't fit for whatever reason — race, gender, whatever — and you're clever and motivated and have some sense of agency, of course you're going to search out other ways of having an impact and being involved,' says ANNE BURDICK, a graduate professor at Art Centre, who studied under Wild and alongside Davis and de Bretteville.

Today, these

trailblazers are still considered the strongest voices in design education, and are at the centre of a tight-knit group of female educators who lead the nation's academic agenda. Many of them head graphic design programs at the influential graduate level. Others are revolutionising the role of design through research. And many more female design educators have taken on national leadership roles, where their writing and contributions through organisations are devoted to an ongoing dialogue about the way not just education, but also design, must evolve.

Making it personal

One of the most powerful and controversial effects that woman educators have had on the discipline overall is the emergence of a type of work that is more personal. This is directly derived from elements of the feminist movement when many educators gravitated toward subjective interpretation, encouraging diversity and multiple perspectives. While definitely not an inherent 'feminine' approach, there's a method embraced by many of these women that focuses on the development of the individual, and ensuring that students can append meaning to their work.

‘Design thinking evolved when women became more prominent as design educators,' says Tenazas. She points to a comment made by the late Scott Makela who noted the influence of female educators like Greiman, McCoy, and de Bretteville as the change factor for design in the mid-80s. 'This more personal work would not have happened if more teachers were male. Scott said that he saw a whole generation of students, even male students, where the thinking shifted because it's no longer about professional practice alone but personal voice and personal history,' Tenazas adds.

‘I always try to approach each student as an individual and help each cultivate his or her unique capabilities as they acquire fundamental knowledge and skill sets', says McCoy. 'I also encourage each student to develop his or her own voice — to learn to articulate their thoughts about design and to participate in discussions equally with others.'

`To encourage students to make work that means something requires more than amplifying opportunities for self-expression, and this is what I personally feel needs to happen — and is happening — at many schools', says Helfand, a Yale professor. 'Students need a skill fluency as much as they do many other things.' This cultivation of life skills alongside design skills is also illustrated by the ex-ample these women set for their students. There are varied ways of incorporating their roles as designers into their roles in the world, and many of them have found ways to seamlessly integrate their personal lives into their practice. An exceptional number work with their husbands; others have found a way, whether through their teaching schedules or in flexible studio environments, to raise families within the context of their career. 'One thing that makes education attractive for these women is piecing together a career, academic life, and the scholarly need of wanting to know more', says Gonzales Crisp. 'Their practices show it, their lifestyles show it, the fact that they have master's degrees in design shows it.' And beyond the multi-faceted approach to their practice, they're also showing the benefits of design as a basis for an enriched life experience.

‘I think that these women are not just concerned with cultivating professionals, but opening up a way for a generation to have wonderful lives,' says Sandhaus. `That's a huge distinction. They don't look at the discipline in a narrow way, but the skills they learn as designers can move laterally.'

Page 361 -

Beyond The Glass Ceiling

Astrid Starvo

Definition. The United States Federal Glass Ceiling Commission defines the glass ceiling as "the unseen, yet unbreachable barrier that keeps minorities and women from rising to the upper rungs of the corporate ladder, regardless of their qualifications or achievements."

People to look into:

- Jane Atche

- Ethel Reed

- Kathe Kollowitz

- Dora Hauth - Trachster

- Catherine Zask